The Boston Railroad Photo Car: An Interim Report

- Tim Greyhavens

- Aug 3, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 15, 2025

Of all the mobile photography studios that roamed the nineteenth-century American West, none was more prolific and, thus far, more enigmatic than the Boston Railroad Photo Car. The BRPC, as I’ll refer to it here, was not just another itinerant operator rambling around in the relative luxury of a specially outfitted railroad car—it was a major business enterprise, complete with an East Coast overseer, multiple studio cars, and dozens of photographers, retouchers, and darkroom assistants. From about 1888 to 1900, as many as thirteen Boston Railroad Photo Cars traveled the iron tracks from Montana to California to Kansas and many points in between. For the past six months, I’ve been digging through troves of online and brick-and-mortar archives to uncover the details of this fascinating operation. I don't have all the answers yet, but here is what I know so far. Maybe someone out there can add to this knowledge.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, railroads rapidly became the dominant means of long-distance travel in America. The first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869 by the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads, connecting Omaha, Nebraska, to Sacramento, California, on a route that traversed the latitudinal middle of the country. This was followed by a northern route in 1883 and southern routes in 1884. Once these main lines were in place, dozens of connecting lines were built to link smaller cities and especially mining districts with the rest of the country.

Photographers soon latched onto the idea that a single railroad car could provide everything an itinerant artist might want—a well-equipped studio, darkroom space for two or more workers, and in some cases, even living quarters. By the late 1880s, more than a dozen railroad photo cars were traveling around the West, including (but not limited to) Abell's Art-Studio Car in California; the Drum Photo car, Loar’s Photo Car and the Sunflower Photo Car traveling around Kansas; the Chicago Photo Car in Missouri; and, of course, Haynes Palace Studio Car in Montana and beyond. Competition was especially tough in Nebraska, where Hutchings Railroad Car was "doing a rushing business," and Pratt’s Photo Car, Bradley’s Union Pacific Photo Car, and Walker & Barber's Photo Car crisscrossed the same state.

Then, in 1888, a newcomer appeared out of nowhere and changed the game forever. In July of that year, a series of ads ran in the Sherman County Times (Loup City, Nebraska). One ad said, “Baby Day at the R. R. Photo Car. All babies not over two yrs. old taken free. One day only. Friday, July 13. We want every baby in the city at the car on Friday.” The following week, the same newspaper noted, “The residences of E. G. Kriechbaum and W. G. Odendahl were photographed last Sunday by S. S. Denison, manager of the Boston photo car.” From then until the end of the century, ads and notices about the BRPC appeared frequently in newspapers across the West.

A mere four years later, the BRPC self-reported that it was doing an enormous business, with more than 100,000 photos created in just four locations. They also said they were employing six cars that visited "every town and city of importance in the United States and Canada." Many of these claims were likely exaggerations to help boost business, but there may be some truth to at least a few of them. In most towns where they appeared, they advertised prices that were substantially lower than those offered by local studios. Their standard pitch was to start most locations with a "baby day" in which every mother could get a free finished cabinet card portrait of her child. Undoubtedly, they enticed more than a few of these customers to buy additional copies or try different poses.

Who Operated the Cars?

To start tracking (pun intended) the BRPC, I compiled a list of the reported operators of the individual cars, beginning with the above-mentioned Samuel Sidney Denison (1851-1912). He is thought to have learned photography in Omaha, Nebraska, where he was listed as a retoucher in the 1883 city directory. A BRPC ad in September 1888 claimed "S. S. Denison, Manager. One of Zerony's Students." There is no known photographer named Zerony, but this might have been an attempt to use the name of famed New York photographer Napoleon Sarony to lend credibility to the photo car's reputation. However, there is no evidence that Denison ever worked for Sarony.

The BRPC business model appears to have relied upon hiring a local photographer to manage a single car for either a specified time period or a designated region. Most BRPC cards appear with just the BRPC imprint (no operator mentioned), and most newspaper notices simply refer to the BRPC without any further details. By scouring dozens of newspaper accounts and reviewing more than forty self-identified BRPC cards, I've identified ten operators by name. I suspect there were more than this short list, but again, my research is still a work in progress.

Here are the operators known to me at this time:

Name | Year(s) | Source |

S. S. Denison | 1888-90 | Sherman County Times (Loup City, NE), Jul. 19, 1888 |

J. H. Woods | 1889-90 | Keith County (NE) News, Mar. 8, 1889 / Dawson County Pioneer (NE), Dec. 20, 1890. |

Legerton & Butler | 1889 | Cheyenne (WY) Daily Leader, Jul. 13, 1889 |

Paul Heim | 1890 | Colorado Daily Chieftan (Pueblo), Sep. 29, 1890 |

O. E. Flaten | ca. 1892-95 | Studio imprint on the back of a portrait |

A. P. Frans | ca. 1892-95 | Browning, p. 37 |

John Legerton | 1894-98 | Scott Valley News (Fort Jones, CA), Sep. 8, 1894 |

Charles Hess | 1900 | Billings (MT) Times, Jan. 15, 1900 |

Thomas Ayers | 1900 | Jefferson Valley Zephyr (Whitehall, MT), Jun. 1, 1900 |

G. W. Haling | 1900 | Neihart (MT) Herald, Sep. 29, 1900 |

Although that BRPC claimed to have operated as many as thirteen cars (see "By Order of the General Manager," below), most card imprints feature the just the name "Boston Railroad Photo Car" or "Boston R. R. Photo Car." Two known cards have imprints that say "Boston Railroad Photo Car No. 3" or "Boston Railroad Photo Car No. 4," but no additional numbered cards are known at this time. I'm continuing to research each of the above operators for additional clues.

Boston Photo Car or Boston Art Company?

To further complicate the origins of the BRPC, in 1896 ads for the cars began to appear with the additional name, Boston Art Company. The exact connection between the two is uncertain (for example, see the above ad). A few notices about the company appeared in Boston newspapers during the 1890s, but they did not provide any insights into the business relationship:

Feb. 24, 1891. "The partnership heretofore existing between Charles I. Fowler and E. J. Edgerly, under the name of the Boston Art Company, is hereby dissolved, and all persons are cautioned against trusting said firm, as I shall pay no debts contracted from this date. E. J. Edgerly." (Boston Globe).

Nov. 2, 1892. "New Art Company. The Boston Art Company filed an application this morning with the Secretary of State to be incorporated. The capital stock is $10,000 and the par value is $100. The application is signed by Edward C. Merrill, Rodney D. Morgan, and Henry L. Weston, officers of the company". (Boston Evening Transcript)

Oct. 18, 1893. Ad: "Did You Hear the Horn? It is blowing for the best place in Boston to get your pictures framed. When you call, bring this advertisement; it is worth one of our Silver Cabinet Portrait Frames. Boston Art Company, 57 Washington St."

The last known reference to the Boston Art Company appeared in the Neihart Herald (MT) on September 29, 1900. It said, "G. W. Haling, operator at the Montana Central depot here, has resigned his position and accepted a place with the Boston Art Company, which travels in its own special car."

I reached out to the Boston Public Library, Harvard University Library, and Yale University Library to see if they have any information about the BRPC or the Boston Art Company, but their reference staff stated they have no records in their catalogs about either company.

By Order of the General Manager

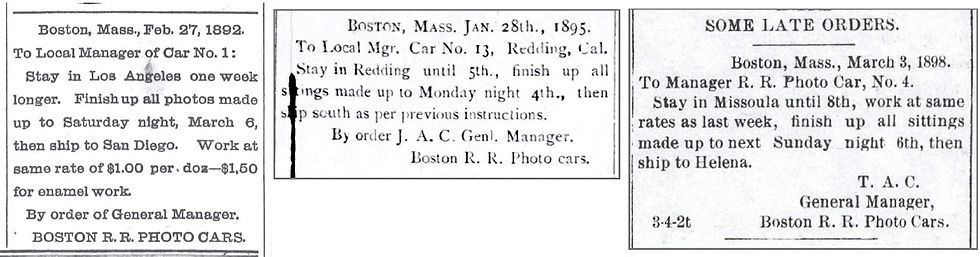

Despite the extensive documentation of the BRPC’s travels, several unanswered questions remain about who was behind the operation. An 1892 Los Angeles Times article offered this tantalizing hint: “A few years ago, when a Boston firm of photographers fitted up a car and started out over the Eastern railroads to get business, it was generally regarded as rather a visionary undertaking in which there could be very little if any profit” (see "Here at Last" above). During that same decade, several additional newspaper notices provided more clues (see notices below). These substantiated the claim that a Boston firm was behind the BRPC, yet none of the notices offered any concrete details. Three notices included what seemed to be the initials of the company’s general manager: J. A. C. (or in one case, T. A. C., which might have been a typo).

With this information, I turned to Chris Steele and Ronald Polito’s Directory of Massachusetts Photographers, 1839-1900 (now available online). Unfortunately, this otherwise authoritative resource does not have a single reference to BRPC or the Boston Art Company. I also scoured the listings in the book for photographers whose last name begins with “C” (as in J. A. C. or T. A. C.), but I found no entry that matched or was close to the right combination of the three letters.

After dozens of searches in western newspapers, I've found just five of these notices (although some appeared on multiple days in the same newspaper). Each provides operating instructions for a specific car, and the level of detail in the instructions suggests that someone in Boston was keeping a close watch on the movements and output of each car. Given the number of cars that appeared to be operating at the same time, one has to wonder why just this handful of notices have turned up. Perhaps the car operators usually were kept up to date by telegraphs they picked up at each stop, and the Boston company resorted to newspaper notices only when an operator failed to reply to a telegraph. Regardless, it seems clear that the BRPC really was the brainchild of a Boston-based company.

Questions to (Hopefully) Be Answered

Who were the Boston photographers/business people who started and managed the BRPC?

Equally important, why is there no document trail (digital or otherwise) that leads us to them? They must have been prominent enough to have the funds to start and manage the operation for twelve years, and it's odd that no one appears to have taken public credit for what must have been a very successful business.

Why did the operation end in 1900? We know that the enormous popularity of the recently introduced Kodak cameras changed the viability of many photography business models, so perhaps the market for the scale of their work eventually disappeared. It's also possible that one or more of the managers passed away or simply lost interest.

We may never know the answer to these questions, but for me, that's part of the fun. If you have any additional information or thoughts about BRPC, please get in touch with me (info@timgreyhavens.com). I always enjoy learning more from other mystery lovers.

Key Sources

Robert O. Brown, The Collectors Guide to 19th-Century Traveling Photographers (online).

Chris Steele and Ronald Polito, Directory of Massachusetts Photographers, 1839-1900 (online).

Carl Mautz, Biographies of Western Photographers, 1840-1900. Carl Mautz, 2018.

Comments